I answered without hesitation.

“I never decided to become a writer,” I said. “Writing picked me.”

That’s the best I can explain it. One day I was reading Nancy Drew books, the next I was making up my own Nancy Drew-like character and writing a book of my own. An amateur effort, unquestionably, but I was maybe 11 years old.

From there it was simply me paying attention to my strengths and to what made my heart soar. Grammar, spelling, reading, writing. Being told in ninth grade by Mrs. Cerniglia that my story about my adventures as an inch-high person was really good. Knowing intuitively in high school that if there’s a class called Creative Writing, I’ll be in it even when I have no idea what it is. Being spurred on by one ‘A’ after another in my first college composition class where Dr. DeMeritt helped me discover and then fine-tune my persuasive writing gift.

There was never a doubt. Sure, I deviated from my writing path a few times over the years, but I’ve always found my way back.

Writer is who I am.

So why this? Why now?

I’m 54 and I know by now that when I want to sort through something, the best possible thing I can do is write about it. It brings clarity. It expels demons. It stirs my soul. And since answering that question over a recent brunch date, I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it.

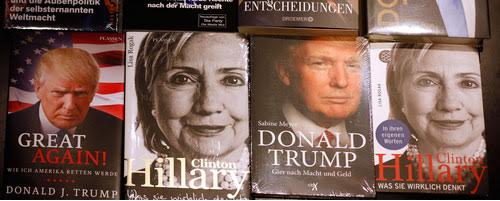

With all that has happened in journalism since I studied it in the 1980s and then worked in it through the ‘90s, seeing colleagues steadily leaving the profession because of the scarcity of jobs and the questionable ethics of the online era, and then personally taking on the challenges of being a freelancer, perhaps this is the perfect time to stop and reflect on the why. What in the world keeps me here?

I know the answer. That girl who was buoyed along by her heart and her teachers. This is for her. And you know how I know this?

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.

Because if Francie Nolan can persist in being who she is through poverty, achingly hard work, loss, and very little encouragement, darn if I can’t stay the course.

One of the things that’s challenging about being a freelancer is the lulls. I’ve had (and have) some rewarding, amazing writing gigs in the last decade. Each one has strengthened me and made me a better writer, a better person even. But in between gigs, oh, how that tests even the most determined and sure-footed among us. This is me now.

I don’t believe for a second it’s a coincidence that I recently picked up a classic book that I’d always meant to read. I tend to go with the idea that it came on my radar because I’m supposed to be reading it at that particular moment in time. So yes, it took me until my 50s to actually understand the cultural references to a beloved character named Francie, one that I became invested in on page 25. This little girl had waited all week to arrange herself on her fire escape with a rug, a pillow, a book, a glass of water, and peppermint wafers arranged in a bowl.

“Once out there she was living in a tree,” author Betty Smith writes. “No one upstairs, downstairs or across the way could see her. But she could look out through the leaves and see everything.”

I get her, right down to the joy in isolation and the giddy feeling of observing.

“Francie stared at the oldest man,” Smith writes. “She played her favorite game, figuring out about people.”

And the realization that dawned when she learned to read:

“From that time on, the world was hers for the reading.”

And the fire in her belly that told her early on she must fend for herself:

“It was a good thing that she got herself into this other school. It showed her that there were other worlds beside the world she had been born into and that these other worlds were not unattainable.”

And the exhilaration of that first byline and every subsequent one:

“From time to time she’d glance at her name in print and the excitement about it never grew less.”

I found myself cheering on a character because I saw so much of myself in her. Aside from Francie’s delight in sour pickles and her dabbling in ballroom dance, as I turned the pages I realized we had much weightier things in common.

A big one was the pageantry and tradition of Catholicism, but also its built-in guilt and shame. Francie questions God and it comes from a smart, heartfelt place. She also takes on a teacher who tells her not to write about poverty, starvation, and drunkenness, and prefers she write stories about beautiful things. In the most compelling ways, Francie walks the line between obedience and respect for authority on one side, and what her gut is telling her on the other.

She is optimistic, idealistic, stubbornly ambitious.

At one point while just a teen, she is working in a factory and thinking, “This could be a whole life.” Later in that train of thought, the narrator says, “Fright grew in Francie.”

I know that fright well.

But I also know it’s what spurs those of us with a fire in our belly to keep going, to stay true to who we are.

“It was something that had been born into her and her only – the something different from anyone else in [her] two families,” Smith writes. “It was what God or whatever is His equivalent puts into each soul that is given life – the one different thing such as that which makes no two fingerprints on the face of the earth alike.”

Writing picked me. I need to heed that.