“Is this for you?” asked Pete Hamill.

“Yes,” I said.

“What’s your name?”

His pen was poised.

“It’s Nancy … and I think you can guess why.”

He looked at me again, this time with a smirk.

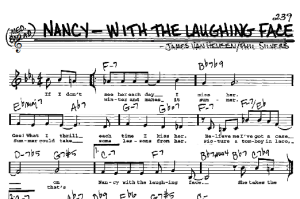

“Because you have a laughing face?”

I laughed as if to prove it.

The truth is I’m named Nancy Ann after my two grandmothers, but my father likes to tell me he won my mother over to the idea by playing Frank Sinatra’s Nancy (With the Laughing Face). He had just told me the story again on Thanksgiving.

When I called to tell Dad about my exchange with Hamill, I could hear him smiling through the phone.

There was so much more I could have shared with him about my evening at Little City Books, as the panel assembled to celebrate Sinatra’s 100th birthday (December 12) was riveting. However, my father is 100 percent about feeling the music, not so much about the learning. I, on the other hand, happily absorbed the intellectual discussion.

While I’ve written about him before, it’s always been in the context of growing up. His music was a fixture in our house. My parents’ wedding song is by Sinatra. Before I left suburban life in Central Jersey and moved because of a job I landed in New York City, I blared New York, New York on my car radio, over and over. It was 1998, a mere three months after Sinatra died. I had not planned on moving to Hoboken, his birthplace, but apartment prices in Manhattan weren’t in my budget.

Now, 17 years later, living in close proximity to Sinatra Drive and Sinatra Park, I no longer see this complex, legendary man strictly through the prism of my father or my upbringing. I have developed my own take on Sinatra.

****

“I’d rather do time in Attica than be 15 again. I didn’t know whether I was coming or going.”

Reading these words by Frank Sinatra — in Hamill’s book – I felt for the first time a kinship with the man. Not just admiration or a flash of inspiration. Not simply a moment of entertainment or dance-y joy. But real, honest-to-goodness kinship.

You couldn’t pay me to go back to my teens. I always hear people long for those ‘good old days’ when there were no responsibilities and I’ve never been able to relate. Neither could Sinatra.

The more I read Hamill’s book, the deeper my connection with the singer felt.

“I’d be in the bus, and the guys’d be sleeping or drinking or talking,” [Sinatra] said once. “And I’d look out the window and see these houses with the lights on and wonder how they all lived. The houses looked warm. Safe. You know, normal. I was still a kid, but I knew that it was too late for me to have that kind of life.”

I was surprised at my own reaction to that quote. Clearly that was not meant to be my kind of normal either. Not because it’s too late, but because it’s not a fit. I never set out to be different, but I was never attracted to that kind of normal.

Last week at the bookstore with authors Hamill, James Kaplan, and Will Friedwald as well as moderator Bob Santelli, executive director of the Grammy Museum in Los Angeles, one panelist noted that he’d asked Tina Sinatra, Frank’s daughter, for one word that describes him. She said that was easy – lonely.

While I don’t often feel lonely, what I do relate to is how Sinatra seemed to bounce back and forth from a solitude of yearning to surrounding himself with others.

“Always he would be driven by the solitary’s longing to be reconciled with the world,” Hamill writes.

Plus, even though Sinatra longed to get out of a Hoboken that was much grittier then, the idea of him perched near the Hudson River where I spend many hours reflecting and writing feels special.

“Sometimes he would wander down to the waterfront alone, past the Hoovervilles, past the rustling tracks of the railroad spurs, out to the edge of the piers,” Hamill writes. “There, he would gaze across the harbor at New York, the spires of its skyline rising toward the sky.”

Soaring ambition meets relentless work on one’s craft.

Hamill tells us that Sinatra liked the family feel of being with musicians and this aspect of them:

“With Harry [James], for the first time in my life I was with people who thought the sky was the limit. They thought they could go to the top, and that’s what they aimed for. They didn’t all make it, but what the hell. They knew the only direction was up.”

Couple the solitary aspect of creating and artistry with a burning desire to share that creative work.

“More than many other performers, he needed the audience,” Hamill writes. “He needed to feel a connection with all those strangers, needed them to ratify his existence and his value, needed to feed on their emotions, as they sometimes were nourished by his.”

Yes. My writer gets this. On a soul level. Bring me readers.

Sinatra was a night owl. The evening hours are when I come alive, do my best work.

“It was both a time and a place; to inhabit the night, to be one of its restless creatures, was a small act of defiance, a shared declaration of freedom, a refusal to play by all those conventional rules that insisted on men and women rising at seven in the morning, leaving for work at eight, and falling exhausted into bed at ten o’clock that night,” Hamill writes. “In his music, Sinatra gave voice to all those who believed that the most intense living begins at midnight: show people, bartenders, and sporting women; gamblers, detectives, and gangsters; small winners and big losers; artists and newspapermen.”

We share similar political views. An advocate for immigrants and civil rights. That was Sinatra. He may have done a knee-jerk switch of political party after a rift with John F. Kennedy, but this Italian-American’s underlying world view was clearly liberal.

“When I was young, people used to ask me why I sent money to the NAACP and, you know, tried to help, in my own small way,” Hamill writes, quoting Sinatra. “I used to say, Because we’ve been there too, man. It wasn’t just black people hanging from those fucking ropes.”

It was that depth of feeling, for country, for heritage, for his art, for his loves, that defined him. At the bookstore panel, Friedwald talked about how Humphrey Bogart’s – or rather Rick Blaine’s — vulnerability in Casablanca opened a door for Sinatra’s own vulnerability.

Hamill writes, “Sinatra slowly found a way to allow tenderness into the performance while remaining manly … Before him that archetype did not exist in American popular culture … Frank Sinatra created a new model for American masculinity.”

The artist in me appreciates the vulnerability in his music. The lover in me is delighted that he paved the way for men to feel.

He lived a life that keeps on giving. One hundred years this week. Incredible. I am heartened by this newfound kinship.

****

Under my name on the book he was signing, Hamill wrote:

“Keep the world on a string!”

Ahhhhh.

I’d be a silly so-and-so, if I should ever let it go.

Very well done, Nancy! When I lived in Hoboken I couldn’t get Sinatra off my mind. I learned so much about him, and the history of Hoboken itself through him. But nothing anywhere transcended his way with a song. I’m glad to read and hear so many tributes to him today!

Thanks, Mary Lois! The tributes have been great. I’ve enjoyed events here throughout the year, too, so it’s been extra special.