“We got you out of there.”

That was my parents’ reaction when I moved from a Central Jersey suburb to Hoboken in my late 30s to pursue a professional opportunity. They had, after all, achieved their American dream moving from Jersey City to the ‘burbs when I was seven years old.

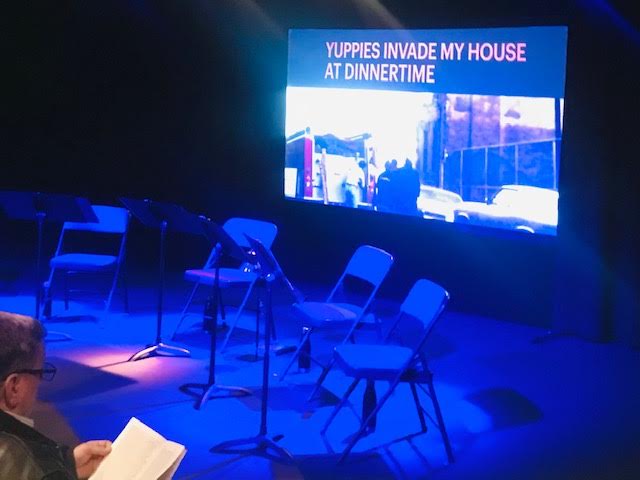

I laughed when they said this. But I don’t think I fully got the impact of those words until I was sitting in Hoboken’s Mile Square Theatre Friday night watching writer Joseph Gallo’s documentary play about gentrification called Yuppies Invade My House at Dinnertime.

While I certainly wasn’t in the first wave of young upwardly mobile professionals to move into Hoboken, I suppose I was technically one when I came in 1998. I had a good journalism job working for “the man” in New York City. I was paying market rent. I was oblivious to the local goings-on, mostly focused on easy proximity to Manhattan as a cultural playground.

Then a few major things intervened – the emergence of the internet and changes in how people consumed news meant about 60 percent fewer journalism jobs, plus the terrorist attacks on 9/11 precipitated layoffs at my corporate media employer. Hence began my unplanned new role as an artist entrepreneur, a venture by no means for the faint of heart.

Which brings me back to Gallo’s play, which at times was like my life flashing before my eyes. His own experience of being an artist, secure in rent control for decades, then thrust into the cold reality of market rents, resonated with me. Like me, he is not a “born and raised” – or B&R, as it’s known here – but he might as well be, such is his passion for the place.

As I head into my 25th year as a Hudson County resident, I too feel much more at home here than I could have anticipated and have a kinship with the B&R. Until recently, my knowledge of my town’s history was sketchy at best. But Hoboken came up sometimes in family stories. My father knew the streets intimately having once been a milkman here. My aunt worked at Stevens Institute of Technology, part of which I can see from my window. My grandmother took a bus from the Greenville section of Jersey City to work at the Maxwell House factory.

At some point I became more entrenched and learned about On the Waterfront being filmed here and of course the lore of Frank Sinatra, both great connectors in chats with my father. Still, if in passing I mentioned my fabulous waterfront walk by the river, my parents would look at each other.

“The Hudson River?” my father would say. And then they’d laugh.

Their experience aside, I have been enjoying that developed waterfront with its sweeping views of Manhattan almost since I got here. Only now, though, am I learning part of the price we paid to have it.

Gallo’s play, with him as narrator and four actors reading different parts, uses pieces of interviews he conducted about what a current Hoboken Historical Museum exhibit calls The Fires: Hoboken 1978-1982, and articles and letters from various newspapers (many from The Hoboken Reporter) about that time.

It was jarring to hear snippets from people who were there describing the fires, clearly arson in many cases but to this day never solved. So compelling with a screen behind the actors lending context to dead families, warnings to leave certain buildings because they were prime targets, the smell of gasoline, the disbelief that human beings would do this to cash out and make a profit. Gallo presented perspectives of Hispanics, Italian Americans, city officials, developers, media and more.

Make no mistake about it, if I went into the theater expecting a history lesson, I came out with a ‘past, present and future’ vibe. They may not be setting fires here these days, but displacement is still the goal of too many in our little haven.

After seeing the play I decided to go down the rabbit hole a little deeper. There are nine video portraits on the Hoboken Historical Museum site as part of the exhibit about the fires. Hearing recent interviews with people who were survivors of the fires or witnesses in some way (a hospital nurse, for instance) moved me to tears several times. I had planned to watch one or two but wound up viewing all nine as a small way of bearing witness. Don’t these people at least deserve that after years of PTSD, grief, nightmares, and the knowledge it is a series of crimes that will likely never be solved?

I cannot imagine.

Janet Ayala’s story takes place on April 30, 1982, at the Pinter Hotel apartments on 14th and Bloomfield streets. She describes being awakened by fire at 3 o’clock in the morning, yelling to her husband, grabbing her baby out of the crib, and barely finding a way out. She lost her mother, stepfather, brother, and nephew in that fire.

The stories reveal swirling rumors whispered among tenants to get out or risk being burned out. There are accounts of fire escape doors made inaccessible. A photojournalist, Bill Bayer, shares his story about the disturbing pattern that kept emerging in the Hoboken fires, then ultimately, a photo series he did after being invited to Barnabas Hospital’s acclaimed burn unit by a physician there who had become fed up with the inaction of law enforcement; he couldn’t believe how many patients were coming from Hoboken.

I am breathless from all I’ve learned. I knew about the fires, but they were just a blip in my head, a headline in an old newspaper, until this week. Somehow, I feel more invested in my town, richer for the knowledge.

Hoboken isn’t for everyone, but it’s a good fit for me. My father died of COVID in 2021 and later that year the town erected a statue of Sinatra at the waterfront mere steps from my front door. It makes me feel closer to Dad on some days when I sit on a bench there and crank up Under My Skin. Yes, while staring at the storied Hudson River that Frank himself gazed at from this shore.

Thanks, Joseph Gallo and director Chris O’Connor, for bringing this out in me. My goodness, art is magical. Go see the play.